Tyndall and Albemarle Street

While an editorial in the journal Nature called the RI itself "redundant" and argued for its collection of historic equipment and other resources to be bundled off to the Science Museum, other commentators, including Prof. Bruce Hood have argued, convincingly, for the institution to remain and to remain at its Mayfair location.

Hood argued in the Huffington Post that the Faraday lecture theatre at the RI has become the "iconic home of British science" and a "sacred site".

"[It is] a place that trancends a financial value, a cultural heritage that belongs to the world as much as Stonehenge" writes Hood.

Supporters rightly point to Michael Faraday, a physicist who pioneered the notion that science (and scientists) have a duty to communicate their work to a general audience. It was Faraday who began the famous RI Christmas Lectures in 1825 - they have been broadcast on TV since 1966.

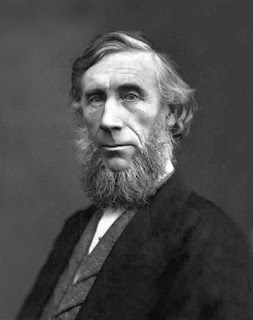

Also worthy of mention here is the noted Irish-born scientist John Tyndall, who succeeded Faraday as Director of the Royal Institution in 1867.Tyndall was born in County Carlow in 1820 and studied in Britain and Germany, making significant contributions to a variety of fields including magnetism, heat and atmospherics. However, like Faraday, one of his great contributions was in science communication.

Having joined the RI originally in 1853 (he was unsuccessful in applying for jobs at Galway, Cork and elsewhere), Tyndall delivered the RI Christmas lectures 12 times, from 1861 to 1884 and, like Faraday, was conscious of the need for science to be communicated to the public. He had developed his style of lecturing as a schoolteacher and in later years, according to Meadows, found that a drink before lectures improved his performance.

In a preface to the third edition of his book Heat: A Mode of Motion, Tyndall noted that his work on public lectures allowed him an opportunity to acquaint himself with the "knowledge and needs of England".

Tyndall and his contemporaries "deprecated and deplored the utter want of scientific knowledge, and the utter absence of sympathy with scientific studies, which mark the great bulk of our otherwise cultivated English public".

He was convinced that "if a scientific man take the trouble, which in my case is immense, of thinking and writing with life and clearness, he is sure to gain general attention. It can hardly be doubted, if fostered and strengthened in this way, that the desire for scientific knowledge will ultimately coerce the anomalies which beset our present system of education".

|

| John Tyndall |

While it is not my place to tell the British scientific community what to do, Prof. Hood is correct in pointing out that the RI building is not just an important site for British science, it is of worldwide significance and would ideally be maintained for its current purpose. Would the worldwide art community permit the French government to sell off the Louvre or the British government to put the National Gallery up for sale?

In a recent letter to The Times of London, David Attenborough, along with 21 scientists wrote that "If Britain loses the Royal Institution, it loses a part of its past. This institution, with its iconic lecture room where almost all the Christmas lectures have been delivered, is just as precious as any ancient palace or famous painting".

"This must not happen in a country that cares about culture, and least of all in one that pins its hopes for future prosperity on a new generation of scientists and engineers."

There is something to be said about public engagement with science being more than just about bricks and mortar. Hands-on experimentation and web-based interaction are all tremendous leaps forward that, I'm sure, Faraday and Tyndall would have approved of. However, they do not replace a rich cultural heritage of science and scientific communication that is represented by the RI building at Albemarle Street, which is of enormous value besides its monetary one.

You can sign a petition to save 21 Albemarle Street as the home of the Royal Institution here.