Thursday, April 26, 2012

Saturday, March 24, 2012

GM Potato set to be planted in Ireland

In a statement issued at the end of February, Teagasc (the Irish agricultural development agency) announced that they are to seek a license to carry out field trials of GM potatoes as part of the AMIGA consortium - a group including representatives of research bodies from 15 EU countries.

Late Blight, caused by the fungal-like organism Phytophthora infestans, decimated the Irish potato crop in the 1840s leading to the Great Famine. Since then, it has remained a problem for Irish farmers, requiring chemical fungicides to be used to maintain Irish potato yields. GM potatoes have the potential to protect the potato plant from Late Blight attack without the necessity for large amounts of fungicide to be applied.

The potato variety Desiree was transformed withe the Rpi-vnt1.1 gene which confers broad spectrum resistance to Phytophthora infestans. That gene, along with its own promoter and terminator regions were taken from the wild potato species Solanum venturii and inserted into the cultivated potato using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation.

In a statement released last week, Irish Organic Farmers and Growers Association (IOFGA), called the experiments planned for Teagasc's Oakpark headquarters a waste of taxpayers money. "In light of the fact that Teagasc has lodged an application with the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) for a licence to grow GM potatoes at its headquarters in Oakpark, IOFGA are demanding that Teagasc be held accountable for their decision to waste taxpayers money on this project."

|

| File Photo: Minister Ruairi Quinn at an Anti-GM event last year |

The statement ends by accusing Teagasc of pedalling an "unwanted technology":

"In this austere economic climate we need to end wasteful public spending immediately and enforce accountability on those who continue to do so."

Unfortunately, it seems the lobby group for the organic industry, is jumping the gun a bit here.

The funding comes directly from the EU's FP7 research programme - a €50 billion fund specifically designated for research and technological development. There is no question of further money coming from Irish taxpayers.

No matter where the money comes from, there is also a wider issue. Teagasc is Ireland's agriculture and food development agency. It is that organisation's role to carry out research leading to a better understanding of agriculture and new agronomic techniques. To accuse such a body of "wasting" money by doing the very thing is was set up to do, is ridiculous. Any arguments for or against GM crops need to be based on firm scientific evidence and that does not simple fall out of the sky.

The field tests to be carried out at Oakpark will look at the impact of GM plants on the surrounding ecosystem and John Spink, Head of Crops Research at Teagasc was keen to point out that the research is "not about testing the commercial viability of GM potatoes".

"The GM study is about gauging the environmental impact of growing GM potatoes in Ireland and monitoring how the pathogen, which causes blight, and the ecosystem reacts to GM varieties in the field over several seasons.”

Mindful of the controversy surrounding trials of GM sugar beet in Ireland in the late 1990s by Monsanto, these new experiments will use a potato developed at Wageningen University in the Netherlands and there will be no biotech or GM company involved. The sugar beet trials ended with a number of the sites being destroyed by a group styling itself the Gaelic Earth Liberation Front.

According to documents submitted to the EPA as part of the licence application, the field experiments are designed to measure the impact of GM potato cultivation on bacterial, fungal, nematode and earthworm diversity in the soil compared to a conventional system; to identify positive or negative impacts of GM potato on integrated pest management systems; and to use the project as a tool for education in order to engage and discuss the issues surrounding GM with stakeholders and the public.

As Teagasc researcher Dr. Ewen Mullins put it: “It is not enough to simply look at the benefits without also considering the potential costs. We need to investigate whether there are long term impacts associated with this specific GM crop and critically we need to gauge how the late blight disease itself responds. This is not just a question being asked in Ireland. The same issues are arising across Europe.”

Speaking to the Irish Examiner, Dr. Mullins remarked: "People are asking about the merits of GM potatoes.At Teagasc, we have a remit to inform people. We haven’t had GM field trials here since the late 1990s. The goal is to look at all of the environmental impacts, and to fill the vacuum that exists currently in terms of impartial knowledge."

An edited version of this article appears on the Guardian's Notes and Theories blog. You can read it here.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 10:17 AM 0 comments

Labels: blight, food security, GM, Guardian, Organic, plant science, Politics, potato, science policy, teagasc

Friday, May 27, 2011

Is Féidir Linn: Obama was right

| |

| Image: WhiteHouse |

|

| Student: Willaim Sealy Gossett |

[Is Féidir Linn: (Irish) Yes we can!]

Enjoy this post? It's been shortlisted for the 3QD Science Writing Prize. Please consider voting for it. It takes just a few seconds. See here for details.

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Live Chat: Communicating research - how can higher education do it better?

I'll be taking part in a live, online event this coming Friday (20th May) as part of the Guardian Higher Education Network.

The panel will be a group of people who are passionate about communicating their research and about engaging the public with their work.

We'll discuss what works and what doesn't; how to reach new audiences; and the skills needed to communicate research effectively.

The online event will run from 1-4pm on Friday 20th May.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 9:20 PM 0 comments

Labels: engagement, Guardian, science communication

Wednesday, February 9, 2011

Is GM now an election issue in Ireland?

This article also appears, in an edited form on The Guardian science blog: Notes and Theories.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 5:00 PM 0 comments

Labels: election 2011, GM, Guardian, Politics

Thursday, September 9, 2010

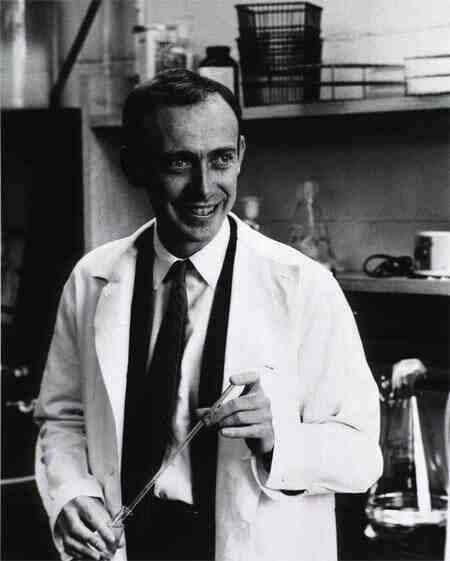

James Watson: A Geneticist's View of Cancer

Speaking at University College Cork last night, while presenting the inaugural Cancer Lecture of the Cork Cancer Research Centre (CCRC), Watson told a packed audience of his ongoing research into finding a cure for cancer at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York where he is now Chancellor Emeritus.

Striking a highly optimistic note, the Nobel Laureate bemoaned some pessimistic cancer researchers who he said were more interested in merely researching cancer and didn't realise that they had an obligation to cure people and to save lives.

"We are nearly there", was his message for the evening, having suggested that the medicines to do the job might already be in use for a variety of ailments, but that doctors and scientists may not have recognised their anti-cancer properties yet.

Watson explained how he initially became interested in cancer research early on in his career. So much so, that he included a whole chapter on cancer in the first edition of his seminal textbook Molecular Biology of the Gene, which was originally published in 1965. The book was based on a a ten-lecture series he had been giving at Harvard for six years to introductory biology students and its format was ground-breaking at the time.

In the preface to the 1965 edition, Watson proclaimed that "it is time to reorient our teaching and to produce the new texts that will give the biologist of the future the rigor, the perspective, and the enthusiasm that will be needed to bridge the gap between the single cell and the complexities of higher organisms. The we may expect hard facts about today's most challenging biological problems: the structure of the cell, the nature of cancer, the fundamental mechanism(s) of differentiation, and how the ability to think arises from the organization of the central nervous system".

Writing in the final chapter of the first edition, Watson explains his hopes for elucidating the causes of cancers and beginning to treat them effectively. In "A Geneticist's View of Cancer", he writes that scientists at the time were just beginning to understand the genetic makeup of the diseases.

Even at the time, just over a decade after the publication of the double-helical structure of DNA, Watson was optimistic that "an understanding of at least some aspects of uncontrolled cell growth may soon be achieved at the molecular level. Such optimism arises from recent, spectacular results on the induction of tumors by viruses".

'Only today are we beginning to gain some confidence that we are close to understanding the essential molecular features upon which the life of even the simplest bacterial cell depends' - James Watson, 1965As a young scientist, at the time, he recognised the obstacles that lay ahead: "Only today are we beginning to gain some confidence that we are close to understanding the essential molecular features upon which the life of even the simplest bacterial cell depends. The jump to an attempt to understand the much more complex vertebrate cell with its thousandfold greater amount of DNA has only begun".

Born in Chicago in 1928, James Dewey Watson received his degree from the University of Chicago in 1947, having enrolled in university at the age of just 15. A PhD from Indiana University followed in 1950 and the young scientist then spent two years doing postdoctoral work in Copenhagen before moving to the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University.

In the Spring of 1953, while still at Cambridge, Watson and his colleague Francis Crick published the results of their collaboration - the elucidation of the double helical structure of DNA.

Watson has had several high-profile roles over the years, including serving as the director, president and chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York where he focused on the study of the genetic basis for cancer. He resigned as chancellor in 2007 after a controversy erupted over comments he made in an interview regarding race and intelligence. He was also involved in the Human Genome Project and was only the second person to publish his full genome publicly online.

'I think the ethics committees are out of control' - James Watson, 2010Prior to receiving an Honorary Doctorate from University College Cork last evening, Watson spoke to journalists telling them that he was in favour of less regulation for clinical trials as this could speed up the process of finding a cure for cancer: "We're terribly held back on clinical tests by regulations which say that no one should die unnecessarily during trials; but they are going to die anyway unless we do something radical. I think the ethics committees are out of control and that it should be put back in the hands of the doctors. There is an extraordinary amount of red tape which is slowing us down. We could go five times faster without these committees".

Speaking in an introductory address to the gathered audience, Prof. Gerald O'Sullivan of CCRC praised Watson: "His accomplishments and contributions transcend boundaries, disciplines, and generations. One of the greatest scientists ever, he is also a respected leader, a gifted administrator, a brilliant author and a beacon in the Gaelic Diaspora". Watson mentioned his mother's family during his speech who left Co. Tipperary during the famine.

Prof. O'Sullivan continued, "Hopefully mankind will also constructively use its increasing technical capability to live peacefully. If so, the humans in future millennia may not know of many from our time but they will know of the structure of DNA and of Watson and Crick as by then the ramifications of its discovery will have impinged on life in ways that we cannot yet imagine".

An edited version of this article appears on the Guardian.co.uk Science Blog. You can read it here.

Parts of the post were also reported in the Wall Street Journal. You can read it here.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 8:45 AM 0 comments

Labels: Cancer, CCRC, DNA, Guardian, James Watson, UCC, Watson and Crick

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

EC has "failed science and failed itself"

| Canola in Alberta, Canada |

The EC plan announced in July is to allow individual member states the freedom to "allow, restrict, or ban" the commercial cultivation of GM crops in their jurisdictions. The EU will still need to authorise the growth of such crops in the same way it always has, however now the individual member states can ban production of the crop even if the EU says it is perfectly safe to grow and consume.

In this respect, the European Commission is, on the one hand putting its faith in, what it calls, its own "science-based GM authorisation system" and on the other saying to member states that they can ignore the science and plough on regardless with anti-GM bans.

With one decision, the EC has cast doubt on its own GM authorisation system; has refused to back the overwhelming scientific evidence and has handed an own-goal to those who would ban GM crops without any research into their potential benefits, or indeed problems.

Undoubtedly, the GM authorisation system in painstakingly slow. Take for instance the eventual go-ahead received by German chemical company BASF for the production of its 'Amflora' potato variety. With altered starch-producing properties which makes it easier to extract the starch for industrial uses, the company spent 13 years guiding it through the European testing and authorisation procedures.

'there can be few who say that the process is not thorough enough'However, despite the system being slow, there can be little doubt that it is very thorough and very conservative in its decision making. GM opponents will, of course, question the final result in some cases, but there can be few amongst them who can say that the process is not thorough enough.

With the recent EC decision, this "science-based authorisation system" remains intact but it will now be just the first stage in the authorisation process. Once a thorough scientific investigation has been carried out at EU level, GM crop producers will need to face a new challenge: that of a heterogenous mix of member states with a range of views on GMO's.

The obstacles at member state level cannot be science-based: the science will have been tested at EU level and found to be sound (otherwise it will not reach the member states). The obstacles at member state level will be political, social and opinion-based.

In announcing the change of course, the Health and Consumer Policy Commissioner, John Dalli confirmed that this decision has nothing to do with science: "Granting genuine freedom on grounds other than those based on a scientific assessment of health and environmental risks also necessitates a change to the current legislation. I stress that, the EU-wide authorisation system, based on solid science, remains fully in place."

In Ireland, for example, the Green Party are now minority partners in government and hold a considerable amount of sway in decision making. Some good news for the environment perhaps, but they have also managed to get a promise to declare Ireland a "GM-Free Zone" written into the current Programme for Government.

Trevor Sargent, the Irish Green Party's spokesperson on Agriculture, Fisheries and Food says that the proposals from Europe "facilitates" the delivery of the GM-Free Zone but he notes: "GM plants do not respect borders and countries like Ireland who are choosing to opt for a GM-free strategy must be facilitated to do so."

Quite how any country could be facilitated in this way is unclear. News from the US last week tells us that GM Canola is capable of spreading over large distances, so it begs the question what would happen if two EU member states sharing a land border were to take opposite views on a particular GM crop?

'The proposed amendments to GM policy will lead to a segregation policy'In addition to a failure to stand up for science, the EC decision appears to be at odds with one of the key goals of the European Union - that of being a free market without border controls between its member states. The proposed amendments to GM policy will lead to a segregation policy with pro-GM and anti-GM states taking sides.

As John Dalli said, the authorisation system based on solid science "remains fully in place". It's just a pity that the EC won't stand over the results of that system, preferring instead to pass the buck to national governments who will be permitted to ban GM crops with zero science to back up their decision.

An edited version of this article appears on the Guardian.co.uk Science Blog. You can read it here.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 1:59 PM 0 comments

Labels: Canola, europe, GM, green party, Guardian

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

55% of public say scientists must communicate more

57% think scientists should put more effort into communicating about their work and 66% believe governments should do more to interest young people in scientific issues. Europeans overwhelmingly recognise the benefits and importance of science but many also express fears over risks from new technologies and the power that knowledge gives to scientists.

For example, a massive 58% of respondents at the EU level agreed with the statement that "we can no longer trust scientists to tell the truth about controversial scientific and technological issues because they depend more and more on money from industry". This figure falls to 36% when responses from Ireland only are considered. Given the Irish government's decision to reduce the amount of exchequer funding available to scientific research, in favour of more input from industry, it begs the question: will the Irish and European public be happy about this? Perhaps not, given the results of this survey, but they are hardly likely to demand higher taxes to pay for purely government sponsored science either.

53%: "scientists have a power that makes them dangerous"Worrying too is the agreement of 53% of the European respondents (46% of Irish respondents) with the statement that, because of their knowledge, scientists "have a power that makes them dangerous". Not potentially dangerous, mind you, but just dangerous, full stop!

Interestingly, when asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement that we depend too much on science and not enough on faith, 29% of Irish respondents agreed. This was down significantly from 41% when this survey was last taken in 2005. Is this an indication of the increased secularisation of Irish society?

With regard to the communication of science, 57% of EU respondents (55% of Irish respondents) felt that scientists do not put enough effort into informing the public about new developments in science and technology. When the data is closely analysed, we see that those respondents who feel that they are not informed at all about scientists feel that scientists themselves are not making enough effort to communicate the message about science.

16%: "newspaper journalists best equipped to communicate science"The majority of EU citizens (63% of respondents) felt that scientists working at a university or government laboratories are best qualified to explain scientific and technological developments. Just 32% of respondents felt that scientists working in industry were best placed to explain these developments. 16% of respondents felt that newspaper journalists were best equipped to discuss such developments.

Research, Innovation and Science Commissioner Máire Geoghegan-Quinn said: "The success of the Europe 2020 Strategy depends on cutting edge science to keep Europe competitive. In turn, that means ordinary Europeans need to back science and keep the pressure up on government and on industry to invest in it. These results show a very high awareness of the importance of science. But they also show that both politicians - like me - and scientists themselves need to explain better what we are doing and why."

Overall, the survey shows that European citizens are fairly optimistic about science and technology - 75% of respondents agree or tend to agree that thanks to science and technology there will be more opportunities for future generations. However, there is a shift towards scepticism compared to the 2005 survey. Judging by the results of this survey, this scepticism could be reduced by more scientists, in particular those in academia, making an even greater effort to communicate their work to the general public.

As Peter Fiske wrote in Nature earlier this year: "Scientists must communicate about their work — to other scientists, sponsors of their research and the general public...searching for opportunities to give talks and lectures — and seeking audiences that are outside one's immediate sphere of scientific influence at, for example, science museums or local civic organizations".

"scientists must communicate about their work" - Peter Fiske"Many scientists are incredulous at how little the general public knows about science and technology" says Fiske, "but scientists do little to address the gap in understanding. Most think that their successes in the lab are manifestly evident, making education about the value of their work unnecessary. Few ever communicate with their elected officials. With the public footing most of the bill, this misguided belief seems naive and undermines those who campaign for more funding.

"Excellent work is a prerequisite for career progress, but is not sufficient by itself. Broadcasting one's accomplishments and exercising the 'active voice' in all aspects of one's work is the best way to earn notice, gain recognition and make the public at large aware of the value of the scientific enterprise."

The full Eurobarometer report (pdf) can be viewed here.

An edited version of this article appears on the Guardian.co.uk Science Blog.

Posted by Eoin Lettice at 12:22 PM 0 comments

Labels: communication, EU, europe, Guardian, Maire Geoghegan-Quinn, public, science

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Communicate Science @ guardian.co.uk

The good people at guardian.co.uk have published one of the articles from Communicate Science as a science blog on their website. The article deals with the recent decision by the EC to allow GM potatoes to be cultivated in Europe as well as consumer opinion on GM in general. The article, which is an edited version of the post that appears on this blog, can be viewed here.

Posted by SW at 12:55 PM 0 comments

Labels: Communicate Science, GM, Guardian, potato

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Second generation GM can't come soon enough

An edited version of this article appears on the Guardian.co.uk Science Blog. View it here.

The starch is used in the paper, textiles and adhesives industries. BASF say that while the starch will not be used in human food, they may use the product in animal feed.

Amflora also carries an extra gene called neomycin phosphotransferase II (nptII) which makes the potato resistant to the antibiotics neomycin and kanamycin. This ‘antibiotic resistance marker gene’ has provoked much debate and is focused on by opponents of GM technology.

In June 2009, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that these marker genes, including nptII are unlikely to cause adverse effects on human health and the environment, but due to limitations to sampling and detection they were unable to be conclusive. They did however re-emphasise that they considered Amflora to be safe.

"Insertion can be achieved by using a bacterium to “ferry” the gene into the plant cell or by blasting it in using a gene gun"The antibiotic resistance marker genes are a remnant of the genetic modification process that produced the potatoes in the first place. GM plants are produced by inserting novel genes into individual plant cells and then growing the plant cells into whole plants in the laboratory. Insertion can be achieved by using a bacterium to “ferry” the gene into the plant cell or by blasting it in using a gene gun. Alternatively, the tough plant cell wall can be stripped off and the gene can be inserted into this “naked” cell.

Whatever way it is inserted, not all of the plant cells treated will successfully take up the new gene and incorporate it into its own DNA; perhaps just 5 cells out of every 1000 in particularly susceptible plants. It is necessary therefore to be able to select those cells which have been modified from those which have not.

By not only inserting the novel gene, but also tagging a marker gene onto it, it ensures that cells which have been successfully modified exhibit resistance to a specific range of antibiotics. In the case of Amflora, it means that only those plant cells which will grow in the presence of kanamycin and neomycin have been successfully modified. The successful cells can then be allowed to grow into whole plants. However, these whole plants will contain the antibiotic resistance genes in every one of its cells.

BASF first submitted its Amflora potato for approval in 1996 but an EU-wide moratorium on GM between 1998 and 2004 delayed the process substantially. When the potato was resubmitted for approval after the moratorium ended, progress was so slow that BASF took the EC to court in 2008 to force them to come to a decision.

The chemical company filed an action against the EC in the European Court of First Instance for “failure to act” and decide on the issue despite the EFSA saying in two separate reports that the product had no harmful effects on human health and was as safe as any conventional potato. The company claimed that the previous commissioner, Stavros Dimas, “unjustifiably delayed” the decision on several occasions.

Now, within weeks of stepping into the role, the new European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Policy, John Dalli, has given the green light for planting to begin. BASF say the potatoes will be grown in Germany and the Czech Republic this year as well as Sweden and The Netherlands in 2011.

Opponents of GM technology have been quick to denounce the decision, with Greenpeace saying that Dalli has “steam-rolled” a decision through. Given that the potato variety in question has undergone 13 years of testing since its first submission, this analogy of a steam-roller might be better applied to the lumbering decision making process in Europe rather than this final decisive move by the new Commissioner.

At the crux of this issue is the consumer’s opinion on GM foodstuffs and GM organisms in general. Consumers genuinely do not see the benefit for them of using GM products.

"there is a need to move beyond GM crops that confer benefits to industry and growers alone and towards second generation GM"For this reason, there is a need to move beyond GM crops that confer benefits to industry and growers alone and towards second generation GM which produces added health and nutritional benefits for consumers. The president and CEO of BASF Plant Science Dr. Hans Kast is on record as saying that the Amflora potato represents a potential added value to European farmers of €100 million annually. The company has also pointed out that they are loosing between €20 and 30 million in license income for every lost cultivation season.

Perhaps I’m being presumptuous, but I can’t imagine many Irish or European consumers laying awake at night worrying about lost revenues for BASF. What Irish consumers are concerned about however, are real and tangible benefits from their foods.

In a study carried out in 2005, 42% of Irish consumers surveyed indicated that they would be willing to purchase a hypothetical GM-produced yoghurt if it had anti-cancer properties. In the same study, 44% of consumers said that they would use a GM-produced dairy spread if it had anti-cancer properties.

These second generation GM crops also have a role to play in developing countries, with the development of biofortified foodstuffs to counteract micronutrient malnutrition among the poor.

Undoubtedly, some British and Irish consumers, in common with their European counterparts are reluctant to consume GM crops and see them grown in their countries. The focus of industry on benefits to the grower and seed producer rather than on consumer-centred benefits will prolong this reluctance and hamper the innovation in our food and agriculture industries which is so badly needed at this time.

Posted by SW at 12:07 AM 0 comments

Labels: BASF, biotechnology, EU, GM, Guardian, plants, potato, starch

PAGES

Popular Posts

It's just a little bit of science!

I'm a plant scientist, so expect lots of plant-related posts but also lots on science in general and science communication.

Enjoy!

Contact: [email protected]

All content, unless otherwise stated, is copyright of Communicate Science and should not be used without prior consent.

Opinions expressed on this blog represent my own views and not those of my employer. Any comments on posts represent the opinions of visitors.

Wade through the scrivenery

Subscribe for Free

Tweet, Tweet

This is me

- Eoin Lettice

- I'm passionate about the need to enthuse, inform and engage everyone in society about science. I'm a full-time researcher and lecturer and a part-time blogger. I'm interested in all things to do with science. In particular, education and communication of science - especially biology. This blog represents my personal views.