"She looks beneath the shadow of my wings"

Living together in Skibbereen, Italy and London for most of their lives, the women pursued a common interest in science and, in particular, in the communication and popularisation of the subject.

Although the family moved to Dublin in 1861 and to Queenstown (Cobh) in 1863, the sisters spent much of their childhood in West Cork. Due to their father's wealth and stature, the family was able to spend the cold winters in Rome (1867 and 68); Naples (1871 and 1872); Florence (1873-76). The sisters made the most of these trips abroad - spending many days reading in the Florence Public Library.

|

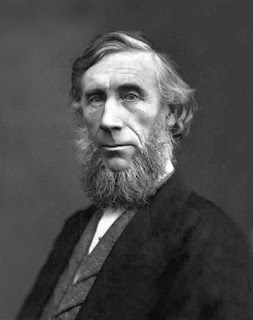

| Agnes Mary Clerke (left) and Ellen Mary Clerke |

The sisters only brother Aubrey noted the defining influence of their father, John William Clerke, on the scientific aptitude of the sisters:

"Although a classical scholar of Trinity College, Dublin", wrote Aubrey Clerke in 1907,"his interests were for the most part scientific".

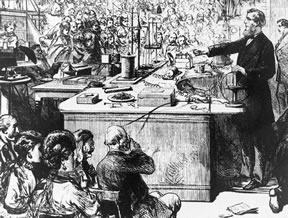

"In our earliest years his recreation was chemistry, the consequential odours of which used to excite the wrath of our Irish servants. Later a 'big telescope' (4 inch aperture)was mounted in the garden, and we children were occasionally treated to a glimpse of Saturn's rings or Jupiter's satellites".

"These trivial things show that it was in an environment of scientific suggestion that our early lives were passed", wrote Aubrey Clerke in a foreword to a booklet recalling his sisters' lives.

| The Clerke family home in Skibbereen |

Agnes Clerke was not a practicing astronomer and her contribution to the field is largely based on her tireless collation and interpretation of data from other researchers and the communication of that research. She could, perhaps, be best described as a science communicator, using today's vernacular.

Despite not working as an astronomer herself, she had, of necessity a vast knowledge of the area and spent a three month period in 1888 at the Cape Observatory (Cape Town) updating her knowledge.

|

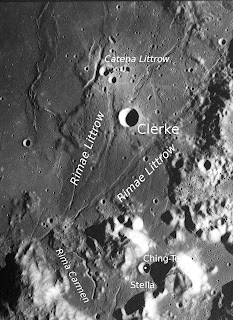

| Clerke Crater on the lunar surface |

A member of the British Astronomical Association, Agnes was also an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ellen Clerke is also known for some astronomical writings including the pamphlets "Jupiter and His System" and "The Planet Venus" but she was also known as a journalist, poet, novelist and commentator on religious issues, with a keen interest in Italian matters having lived in the country for several years.

Ellen's poem Night's Soliloquy, beautifully captures her and her sister's love of astronomy.

Agnes has the distinction of having a crater on the surface of the moon named in her honour. Crater Clerke is about 6 km in diameter and located very close to the Apollo 17 landing site - the last landing of humans on the lunar surface.

Ellen died after a short illness on March 2nd 1906. Huggins notes that "these sisters were lovely and pleasant in their lives and in death they were but little divided". Agnes died on January 20th 1907 from complications associated with pneumonia.