In the run up to Christmas, Communicate Science offers you 20 Christmas Science Facts. We'll post one every day until the 25th December.

New mistletoe species among this year's new discoveries at Kew

As the UN's International Year of Biodiversity draws to a close, scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew are celebrating the diversity of the planet's plant and fungal life by highlighting some of the weird, wonderful and stunning discoveries they've made this year from the rainforests of Cameroon to the UK's North Pennines. But it's not just about the new - in some cases species long thought to be extinct in the wild have been rediscovered.

Professor Stephen Hopper, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew says, "Each year, botanists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, working in collaboration with local partners and scientists, continue to explore, document and study the world's plant and fungal diversity, making astonishing new discoveries from microscopic fungi to canopy giants.

"This work has never been more relevant and pressing than in the current era of global climate change and unprecedented loss of biodiversity.Without a name, plants and fungi go unrecognised, their uses unexplored, their wonders unknown.

"On average, 2,000 new plant species are discovered each year, and Kew botanists, using our vast collection of over 8 million plant and fungal specimens, contribute to the description of approximately 10 per cent of these new discoveries. Despite more than 250 years of naming living plants, applying each with a unique descriptive scientific name, we are still some decades away from finishing the task of a global inventory of plants, and even more so for fungi.

"Plants are at risk and extinction is a reality. However stories of discovery and rediscovery give us hope that species can cling on and their recovery is a very real possibility. Continuing support for botanical science is essential if plant based solutions to human challenges, such as climate change, are to be realised."

This year's new showstoppers include;

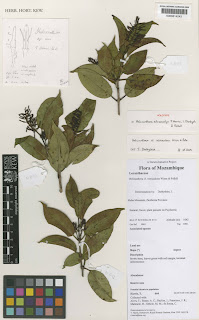

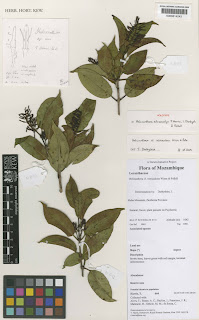

From Africa with Love - Wild Mozambican Mistletoe …

This parasitic, tropical mistletoe was named in 2010, and was first discovered near the summit of Mount Mabu in northern Mozambique, a region which hit the headlines in 2008 when a Kew-led expedition uncovered this lost world bursting with biodiversity. Since then, the team at Kew have worked tirelessly sorting through the hundreds of specimens they collected, and they have described this new wild mistletoe (

Helixanthera schizocalyx), just in time for Christmas!

It was spotted by the expedition's renowned East African butterfly specialist, Colin Congdon, while the team were trekking up the mountain, on a path that took them from the moist montane forest up to where the broad granite peaks break through the dense foliage. Colin quickly realised this species was different from anything he had seen on the mountains in neighbouring Malawi and Tanzania, and on closer inspection back at Kew it was confirmed a new species.

Tropical mistletoes, from the family Loranthaceae, are a great example of biodiversity and the symbiotic relationship between plants and animals. Birds play a vital role in both pollinating these mistletoes, and also distributing the seeds. As birds eat the small fleshy white sweet fruits, the seeds are then wiped on a branch to which they adhere. Once germinated the root grows into the living tissue of the tree to obtain the new plant's nutrients. Tropical mistletoes are also popular with butterflies and in particular the blue group Lycaenidae. These strong links between the plants, their host trees, and various birds and butterflies, shows the interconnected nature of forest species, and the need to conserve all elements in order to preserve the environment.

A Medicinal Wild Aubergine from East Africa…

Commonly known as 'Osigawai' in the local Masai language,

Solanum phoxocarpum was discovered by Maria Vorontsova on an expedition to Kenya's Aberdare mountainous cloud forests. Having researched specimens of wild African aubergines in RBG, Kew's vast Herbarium collections of dried plant specimens, Vorontsova, who was based at the Natural History Museum, London at the time, discovered some unusual unnamed specimens, some of which were unlike any she had seen before. Eager to discover more, Maria set out on an expedition with botanists and seed hunters from Kenya's 'Seeds for Life' project team, partners in Kew's Millennium Seed Bank Partnership.

Many of the old collection locations they visited had been stripped of native vegetation, but after four weeks, the team was successful. They spotted a wild aubergine shrub with distinctive unusual long, yellow, pointed fruits and deep mauve flowers that was indeed a new species. They collected its fruits and set out slicing them open to collect seed for banking. While spreading the fruit's yellow sludge onto paper, so the seeds could dry for long term storage in Kew's Millenium Seed Bank, one of the team noticed that the fruits began to emit a pungent odour and later that day they became ill. It is now believed that this species may be poisonous, and having consulted Kew's historic specimens, it also proves to be used medicinally by local people.

Cameroon Canopy Giant…

A gigantic tree,

Magnistipula multinervia, described excitedly by Kew's well seasoned plant hunter, Xander van der Burgt, as "the rarest tree I have ever found", has been discovered in the lush green rainforests of Cameroon.

Towering above the canopy at 41metres high this critically endangered tree was discovered in the lowland rainforests of the Korup National Park — a hot-bed for new discoveries in the South-West Province of Cameroon. Due to its height, rarity (with only four trees known) and the fact that the flowers hardly ever fall to the ground, it proved difficult to identify and collect in flower. After numerous visits to the four known trees over a period of several years to check if they were flowering and fruiting, the team were successful and using alpine climbing equipment, they managed to scale the dizzy heights, and make their collection, and identify it as new.

Smut and moon carrots - the rediscovery of extinct British fungi…

The long-lost British fungus, bird's-eye primrose smut (

Urocystis primulicola), recognised as a species of "principal importance for the conservation of biological diversity" (BAP review 2007) had not been seen for 106 years until it was rediscovered by Kew and Natural England mycologist, Martyn Ainsworth, during a two hour 'ovary squeezing' session.

Smuts are species of inconspicuous, microscopic fungi that are found inside living host plants, in this case the red-listed wild pink flowered bird's-eye primrose (

Primula farinosa) found in the North Pennines. The bird's-eye primrose smut has co-evolved with the plant and hijacks its ovaries, replacing its seeds with a black powdery mass of smut spores. Concealed in the ovaries, it is only when the bird's-eye primrose seed-pods are squeezed in the late summer, when the seeds are ripe, that this rare smut can be found.

In a similar story, the moon carrot rust (

Puccinia libanotidis) was rediscovered in England after it was believed lost for 63 years. Rust fungi are so called because their spores are often produced in brownish orange powdery masses on the leaves and stems of host plants. The moon carrot (

Seseli libanotis), the plant that hosts this rust, is a red-listed wild plant confined in Britain to the chalky soils of the Chilterns, Gog Magog Hills and the South Downs.

Martyn Ainsworth, Senior Researcher in Fungal Conservation says, "

It is always exciting to rediscover species thought to be extinct but to find one that has been lost for over 100 years, while carrying out a quick survey in a likely spot during a journey between England and Scotland, was an exhilarating 'Eureka' moment. To wipe these rare British fungi off the extinct list is a joy, and we hope that with further field surveying we can now provide a clearer picture of these species' current British distribution.

"

Both these fungal species have been re-discovered on rare British plants, and therefore their conservation is dependent on that of their host plants and their habitats. I'd encourage all field naturalists to get out and start looking for so-called extinct fungi and find out about their relationships with other fungi, plants and animals so we can understand their habitat and conservation requirements better. There are so few of us doing this work, we need all the help we can get."

And finally the biggest new discovery of them all…

The biggest genome in a living species -bigger than Big Ben!

Scientists in Kew's Jodrell Laboratory, as part of their ongoing research into the causes and consequences of genome size diversity in plants, discovered the largest genome of all living species so far - found in

Paris japonica, a subalpine plant endemic to Honshu, Japan.

With a genome size of 152.23 picograms, its genome is 50 times the size of the human genome, and 15% larger than any other found so far —

it's so large that when stretched out it would be taller than the tower of Big Ben! However, having such a large genome may have direct biological consequences, as plants with large genomes may be more sensitive to habitat disturbances and environmental changes and be at greater risk of extinction.

All images are courtesy of Kew and are copyright of their respective owners.